The demise of Labour’s ‘Red Wall’, a bank of parliamentary constituencies located predominately in the Midlands and the north of England, came to epitomise the 2019 general election.

In particular, it was the nature of these newly captured areas that drew the eye. Working class constituencies to their core, these were parts of the country where it was previously considered inconceivable that a Conservative would win.

As the UK heads into its next general election, Britain’s electoral map is slowly being redrawn in a very different direction.

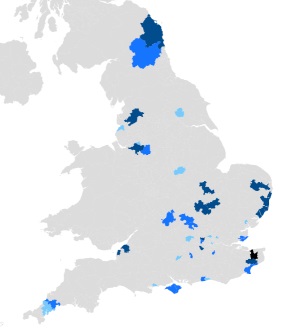

Across the length of England there are some 42 seats that I have herein termed “Blue Wells”.

Each of these is a seat that stayed loyal to the Conservatives throughout the Blair landslide years, but has remained out of Labour’s grasp for at least six decades, and in most cases, ever.

Throughout the course of the last decade, Labour has been making steady progress in each of these “Blue Wells”. In an advance that has gone largely under the radar, perhaps masked by the scale of the wider 2019 Conservative victory, these seats strike to the heart of England’s changing political landscape.

In this year’s general election, even if Labour falls just short of an outright majority, expect 14 of these “Blue Wells” to return a Labour MP for the first time since even their most ageing voter cast a ballot. Should Labour achieve a Westminster majority of 60 or 120 seats, then expect the phenomenon to extend to 29 or 42 seats respectively.

So this prompts the questions, where are these “Blue Wells”, and how is it that they are now coming into electoral play?

The emergence of the “Blue Wells”

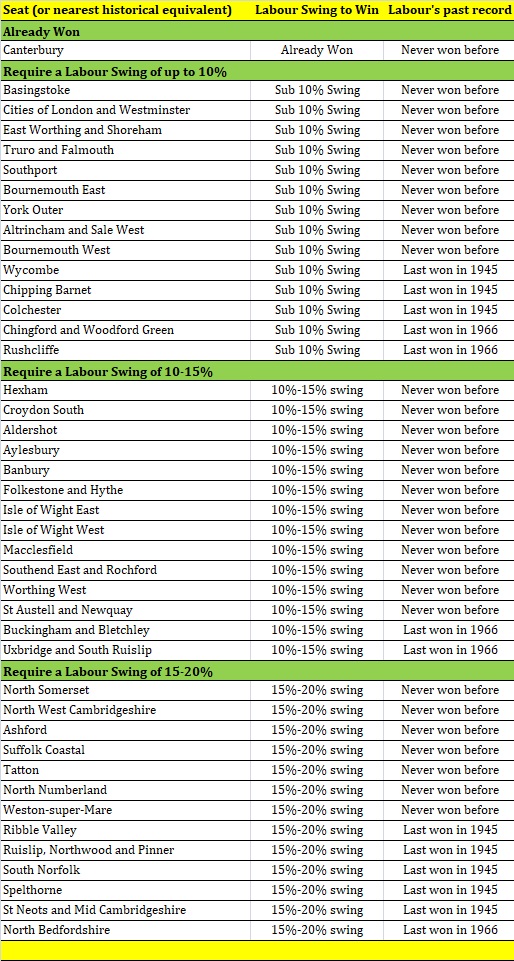

To qualify as a “Blue Well” seat, each of these constituencies (or the largest component of their forerunners in previous Boundary Commission Reviews) must not have been won by the Labour Party since 1966. As per Table (1), each of these seats must also now appear within the party’s grasp.

Table 1 – List of “Blue Well” seats now vulnerable to Labour

Numbering 42 in total, the size of this “Blue Well” cohort is identical to the 42 ‘Red Wall’ seats previously identified by the political scientist, James Kanagasooriam, some 34 of which subsequently fell to the Conservatives (the last being Hartlepool in the 2021 by-election).

Yet these “Blue Wells” are far less geographically homogenous than their ‘Red Wall’ predecessors. They spread down from Hexham and North Northumberland on the Scottish border, to include St Austell, Bournemouth and Worthing on England’s southern coast. They include suburban areas such as Chingford, Croydon South, and Chipping Barnet in north London, Altrincham on the edge of Greater Manchester, and Rushcliffe near Nottingham, but also incorporate stand alone towns such as Macclesfield and Aldershot, and a host of coastal communities such as Weston-Super- Mare and Southend.

As of today just one “Blue Well” seat, Canterbury in Kent, has fallen to Labour. Having never been won by the party before, including even in 1997 when Tony Blair’s ‘New Labour’ won 8 other Kent constituencies, Canterbury turned red for the first time in 2017. Although the city’s substantial student population undoubtedly contributed to this particular “Blue Well” being early to the party, Canterbury exemplifies the wider forces in operation across this cohort of seats.

Why are the Blue Wells now emptying?

Separate to the current gulf in the UK’s opinion polls, it is the steady onset of three separate political forces that have brought these particular Conservative heartlands within Labour’s reach.

Force 1- The evaporation of the Liberal Democrats

The first factor, common across almost all of the “Blue Well” seats, is a dramatic decade long demise in the Liberal Democrats as a local electoral force.

The Cornish seat of Truro and Falmouth is a prime example. In 2010 the Liberal Democrats and Labour were polling around 40% and 10% respectively in this far corner of England. Yet come 2019, those respective polling numbers had almost exactly reversed. Colchester in Essex and Southport in Merseyside exude the same pattern. Where in both areas, the Liberal Democrat recorded 48%-49% of the vote in 2010, a decade later, Liberal Democrat support had slumped to less than 14%.

Within the “Blue Wells”, even during the lowest points of the Corbyn years, the Labour Party has been successfully marching into this Lib Dem void. As it has done so, that Labour surge has also become self-fulfilling. With local Liberal Democrats no longer able to credibly claim that they are ‘Winning Here’, anti-Conservative voters have come to realise that in these seats, it is the Labour party that is the prime challenger to the Conservative.

Force 2 – Schisms in age and class based voting

The second factor siphoning water from the “Blue Wells” is the long standing departure of both middle class, and increasingly also middle aged, voters, from the Conservative tent.

It is regularly remarked that the Conservative’s failure to engage effectively with younger people poses an existential threat to the party’s future. At the time of writing, Labour’s poll lead amongst those under forty was in excess of 40%. Moreover there were signs that this advantage is now spreading into middle age. Amongst voters aged 40-49, Labour’s poll lead now sits at a staggering 36%.

Yet it is when this cohort of younger voters, is mixed with a dosage of middle class voters, that the electoral impact becomes the most pronounced.

Although the Conservative Party was historically regarded as the party of the middle class, this bond has now been firmly detonated. Inconceivable only a generation before, in the 2019 general election, Conservative support amongst A&B social-economic classifications was equivalent to that which it acquired from the D&E groupings. Roll forward to 2024, and polling shows the party to be attracting the support of just a fifth of middle class voters, a quarter lower than its support levels amongst the skilled working class.

This cocktail of age and affluence does not impact on the most rural tranche of Conservative seats, ones where the demographic is slightly older and more working class. However it has become a significant problem for the party across most of the “Blue Wells”, the majority of which are urban and economically active English constituencies.

The Buckingham town of Aylesbury, where the Labour share of the vote doubled during the 2010s, is a case in point. According to the 2021 census the proportion of Aylesbury’s voters falling within the A&B social class groupings was almost half as high again as the national average, with the seat further possessing an average age below that of the country as a whole. And Aylesbury is not alone. The same forces are at work in other once Conservative heartlands, such as Ashford in Kent, Banbury in Oxfordshire, and Basingstoke in Hampshire.

Force 3 – Intra County migration

The third and final factor now bringing this previously untouchable cohort of Conservative seats within Labour’s grasp is migratory. As populations don’t remain still, many of these “Blue Well” seats have seen an influx of hostile voters from up the road.

I have written previously about estate agency data that showed sizeable numbers of anti-Brexit young professionals moving out of fashionable inner London to establish family homes in very specific particular parts of Kent, Hertfordshire, and Surrey. Indeed such is the threat from this urban flight, that Jeremy Hunt has relocated out of the largest portion of his old South West Surrey seat, to compete in the newly created neighbour of Godalming and Ash.

And in different ways, voter movement is also assisting Labour in many of these 42 “Blue Well” seats.

Whether it be traditional Labour leaning Asian voters moving out of West London into towns such as Wycombe, metropolitan Manchester voters moving into leafy Altrincham, or bourgeois bohemians (‘BoBos’) moving along the South coast to Worthing from Brighton, migratory trends posit a political impact.

The Blue Wells – Just one part of the wider mosaic

Unlike Labour’s 42 ‘Red Wall’ seats going into the 2019 general election, the 42 “Blue Well” seats will not in themselves define the outcome of the 2024 contest.

In what is an extremely fragmented electoral battlefield, Labour is also actively looking to regain as many as 30 of its Scottish strongholds that it previously lost to the SNP in 2015, the 34 “Red Wall” heartlands relinquished to the Conservatives, the UK’s 60 traditional swing seats, and at least a further 32 areas that were once won by Tony Blair.

Yet it is these “Blue Well” seats, those that have rarely if ever been won by Labour, that represent perhaps the most interesting and telling component of this year’s electoral background.

Rather than simply being conditioned by events that have occurred since Rishi Sunak entered Downing Street in 2022, these areas of England have been experiencing a demographic and political transformation that dates back to before Rishi Sunak’s even arrived at Westminster in 2015. As detailed above, these are changes that go to the heart of England’s underlying and changing political topography.

These 42 “Blue Wells” once presented the local Conservative MP with an impenetrable fortress from which to pursue their political career.

Now, as a whole host of Labour MPs have only too recently found to their cost in Scotland and the north of England, these 42 “Blue Wells” are the latest exert in the antithesis to the concept of a ‘political job for life’.

Politics.co.uk is the UK’s leading digital-only political website, providing comprehensive coverage of UK politics. Subscribe to our daily newsletter here.