By James Chalmers and Ryan Whelan

What is happening now, and what happens next?

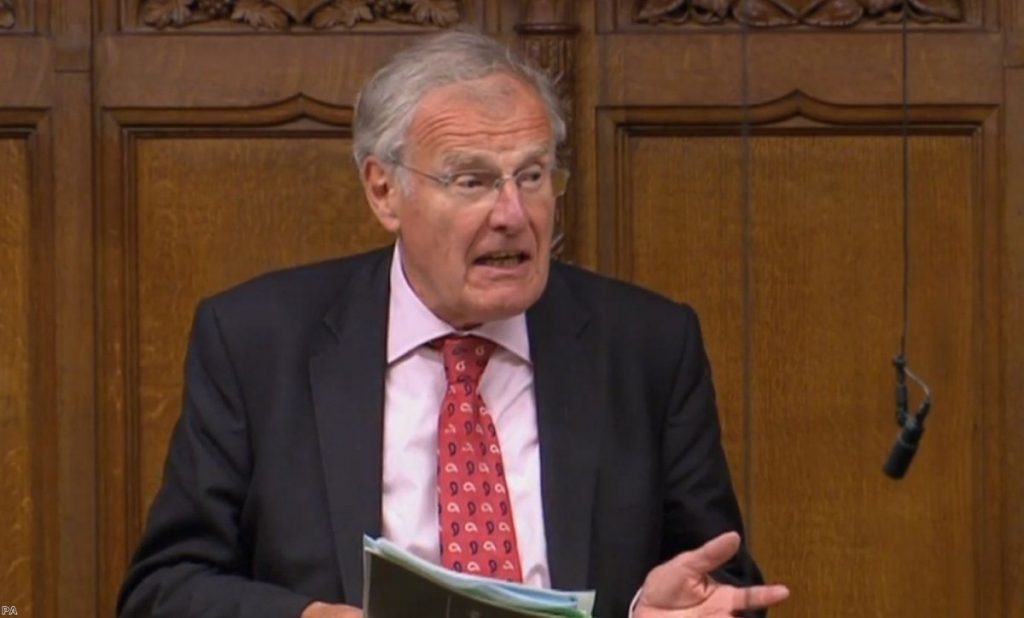

The government has acted swiftly and decisively since Christopher Chope shouted down Wera Hobhouse's private members bill last month. The Monday of the following week – June 18th – saw Theresa May announce that the government would bring forward its own bill on upskirting, which they scribbled up by adopting the text from Hobhouse and supplementing it with amendments agreed with Gina Martin's campaign team. The intention, the PM said, was to have the bill through the House by the end of the parliamentary term.

The government was not slow following through on the prime minister's commitment. David Gauke, the lord chancellor and justice secretary, put the voyeurism (offences) (no. 2) bill down on the Thursday of the same week and government whips found time for its second reading on Monday 2nd July. It has taken the government only 11 business days to put the bill back on track to becoming law.

Next up comes the detailed consideration of committee stage, which will involve the taking of evidence, a clause-by-clause review/analysis, and potentially the suggestion and debate of amendments that will then be voted on by the committee. If it decides to amend the bill, it will be reprinted before returning to the floor of the House for its report stage, at which any MP can suggest an amendment or addition, before proceeding to its third and final reading in the Commons.

What does this special procedure involve?

At its core, the special parliamentary procedure is all about ensuring speed of progression. Time on the floor of the House (even in government time) is difficult to come by. Using this procedure to move the bill to the committee rooms for second reading was a cute way of promptly ensuring that time could be made available for progress to be made.

The government has certainly delivered on its promise to prioritise the upskirting bill. It is now up to the committee as to whether that momentum can be maintained. It certainly seems to be the aim and wish of all political parties, with Labour and the Liberal Democrats being as clear as the government that this gap in the law must be closed promptly.

What is in the government's bill?

The bill, if passed without amendment, would add a new section 67A to the Sexual Offences Act 2003, and so introduce two new voyeurism offences aimed at tackling 'upskirting'. This is the act of covertly photographing underneath someone's clothing without their consent.

Although many cases of upskirting can currently be prosecuted as outraging public decency, the offence cannot always apply. There is an unacceptable gap where the 'two person rule' – requiring that two persons other than the offender should have been capable of seeing the conduct – is not satisfied, a gap illustrated by a case in Northern Ireland last year.

The bill would adopt a similar approach to that taken in Scotland, which made upskirting a specific offence in 2010. The two new forms of voyeurism would cover the operation of equipment or recording of an image beneath another person's clothing with the intention of viewing their genitals or buttocks (with or without underwear), and without that person's consent.

The offences would apply where the perpetrator had a motive of either obtaining sexual gratification, or causing humiliation, distress or alarm to the victim. The maximum sentence following summary conviction will be 12 months imprisonment and/or a fine. The maximum sentence following conviction on indictment will be two years and/or a fine. The bill also provides for offenders convicted of particularly serious forms of the new section 67A offences to be placed on the sex offenders register, which is for public protection rather than punishment.

Why should the upskirting bill proceed so quickly?

Criminal law reform is usually – for good reason – a protracted process. Parliament should not create serious criminal offences, particularly ones as stigmatic as sexual offences, without carefully considering the justification for them and whether they have been formulated correctly. However, the proposed upskirting legislation is unusual and the speed at which the bill is being progressed is appropriate for three primary reasons.

First, the gap in the law that the bill would close is long recognised. The Law Commission of England and Wales noted the gap in 2015. There is no question of any need to establish whether the current law is adequate.

Second, closing the gap in the law is uncontroversial. Lawyers and politicians of all parties agree that reform is required. There is no issue of principle to debate; only a question of settling on the detail of the reform.

Third, as to the proposed reform, the government's bill follows the drafting of provisions implemented in Scotland in 2010, which were themselves designed to fit within a definition of voyeurism which had been taken from English law. While legislation from one legal system rarely provides a simple model for another, the context of the Scottish provisions means they can be fitted into the English legislative scheme with uncommon ease.

None of the above means that parliament can or should simply nod this change in the law through without careful consideration, simply that parliament has something of a head start in the legislative process on this occasion, a fact reflected in the procedure which the government has employed for this bill.

What about calls for the bill to go further?

There are certainly issues of drafting which parliament will want to consider as the legislation progresses but calls for the bill to be broadened to address issues other than upskirting are inappropriate.

This does not mean that these other reforms should not be considered, but they require separate and more detailed scrutiny. For example, possible legislative models on image-based sexual abuse may be found in other jurisdictions, but these models are not capable of being directly fitted into English law in the same way as the 2010 Scottish provisions on upskirting. This means that more extensive work would be required to identify exactly how such provisions should be formulated.

The bill will allow the defects in the law relating to upskirting to be quickly cured. One option – our preferred option – for addressing the broader issues which have been raised would be for the government to commit to engaging the Law Commission (or an ad hoc review body) to report and make considered recommendations on the existing law and the need for reform. But whatever happens, the upskirting bill need not and should not be impeded by these broader, more difficult, questions of reform.

Are there points of detail that warrant discussion?

Yes. Absolutely. Some discussion will undoubtedly be had on motive – voyeurism in Scotland extends both to acts carried out for sexual gratification and those carried out for the purpose of humiliating, distressing or alarming the victim. This was then in Scotland and will now in England be a departure from voyeurism as originally defined in English law, which is limited to cases where the offender acts for sexual gratification – something which commentators have long thought is a flaw in the English model.

The upskirting offence that will be introduced by the bill rightly follows the Scottish model: an offender should not be able to escape conviction because their purpose was to harass the victim rather than to gratify themselves. At the same time, however, it is right that a stigmatic offence, conviction for which may place a person on the sex offenders’ register, should have a clearly stated threshold for conviction, which the motive requirement offers.

Whether the motive requirement should extend beyond sexual gratification, humiliation, distress and alarm is moot. The two most common examples that are given to justify broadening the motive element are that it does not cover those who upskirt to exert power or have 'a laugh'. However, most if not all of these cases can be caught by the bill as it stands. There is no requirement that the prohibited motive be the only motive, and the offender who acts to humiliate, distress or alarm the victim is not somehow given a defence because he does those things to exert power or 'for a laugh'

Some would like there to be no motive element at all – to that end an amendment has been lodged to the bill, proposing that the motive requirement should be deleted, and instead (in cases where the defendant 'records an image') replaced with a provision making it a defence for the defendant to prove that he did not intend to record an upskirting image. While there may be room for debate about whether the motive requirement is appropriately formulated, it would be (at best) surprising if parliament felt it appropriate to define a serious sexual offence in a way that required the defendant to prove that he is innocent, rather than for the prosecution to prove that he is guilty.

James Chalmers is regius professor of Law at the University of Glasgow. Ryan Whelan is Gina Martin's lawyer in connection with her campaign to make upskirting a specific offence and an associate at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP.

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.