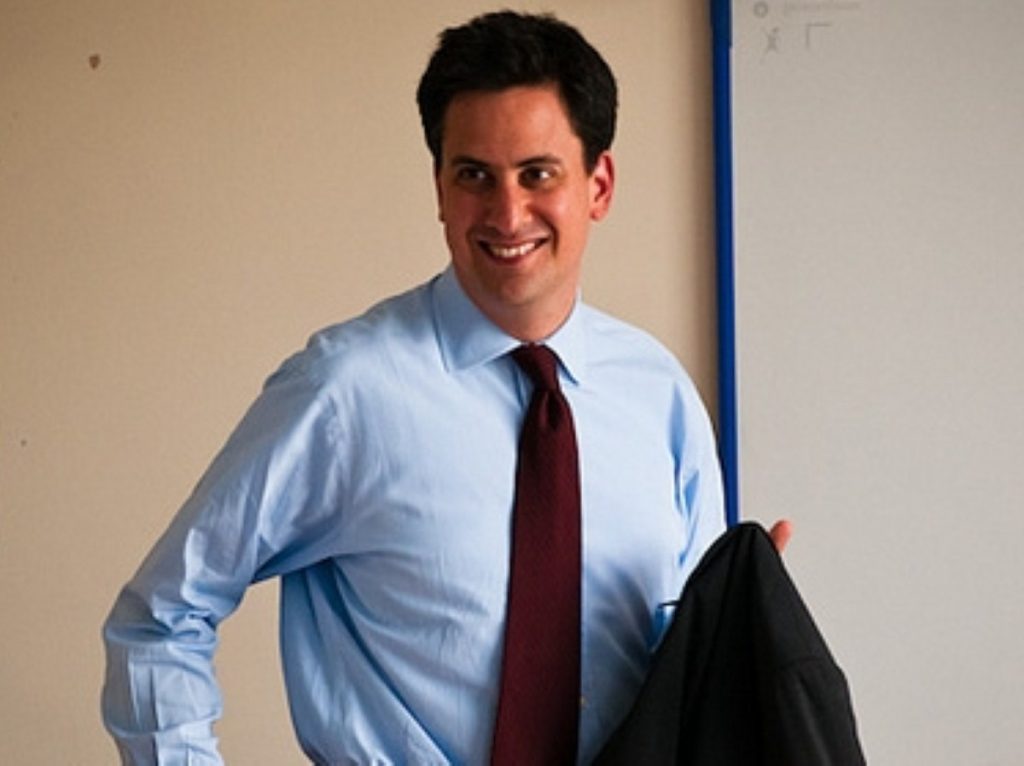

Interview: Ed Miliband

Ed Miliband talks to politics.co.uk about civil liberties, Tony Blair and why he voted for ID cards.

By Ian Dunt

Ed Miliband is nice. That’s the first thing I ever heard about him. It came from a civil servant in the Department of Energy and Climate Change (Labour had a knack of creating government departments with ugly, stilted names and this was one of them). He was the first man to become energy secretary, and the internal reaction to him was gushing.

Even those who criticise him are forced to dress it up as flattery – hence Alastair Campbell’s assertion that he is too nice for politics. Tony Blair’s memoirs spared the younger Miliband his less-than poisonous pen. He’s the only one of the Brownites who gets away with some respect in the book. No-one has a bad word to say about him. Even his political enemies think he’s alright.

But he can’t be all that. People who go from fledgling MP to Cabinet secretary to leadership frontrunner in five years rarely are. He’s also got a dodgy record, given his current rhetoric. He may be singing the praises of civil liberties now, but once upon a time he voted for 90-day detention and ID cards. He was, after all, the man that wrote the Labour manifesto at the 2010 election. There wasn’t much talk of civil liberties in that.

All of this rather falls to the wayside when I meet him. He really is rather nice. He has a presence, but it’s subdued. He could almost pass for normal. Normal is officially a good thing in Westminster, of course. In the outside world, it’s the used to designate a bore. In Westminster it designates a winner. It’s a vanishing commodity in politics, one to be carefully bottled and preserved. Ed Miliband isn’t normal – he’s a politician, after all. But he is something close. He listens to questions, he bites his nails, he makes eye contact at predictable and non-invasive intervals. He has a relaxed and reassuring manner about him.

Perhaps he can afford to be relaxed. The growing consensus in Westminster is that he’s going to win. He seems positive too. “I feel I’ve got the momentum in this campaign,” he says. “I feel like, particularly in the last few weeks, I have an increasing sense of things moving in our direction.”

He’s particularly effusive about his methods, which have seen the team adopt an impressive and politically revealing campaigning system. “Basically I think we’ve had a secret weapon in this campaign, which is the army of volunteers have had up and down the country,” he continues.

“We’ve had four or five thousand people making phone calls on my behalf. We’ve had phone banks in over 20 cities most evenings and we’ve had a system where for the last three months anyone can make a phone call on my behalf just from their home, using an online database system. We think this the largest field operation that any political campaign has had in a leadership election in the history of British politics.”

Most of those volunteers are young people who aren’t card-carrying Labour members. It’s a product, he insists, of his position as the ‘change candidate’, the man who signals a break with the past. “New Labour was right for its time but we need to move on, and all the attacks on me from the New Labour establishment have helped crystallise that message,” he argues.

The trouble is, Ed Miliband is no less associated with New Labour than his rivals, even if he was the first to disassociate himself from it. I point out to him that despite his civil liberties rhetoric he once voted for ID cards.

“Yeah, I did,” he replies. “I was part of the government and I take collective responsibility for that. And I say in this campaign, I take responsibility for what went right and what went wrong. But that’s what you do. You have a choice in government – you can either take collective responsibility and stay in government or you can resign. I thought what the last Labour government did overall was really good. I thought we did great things for the country and I was proud to be a part of that. So you know – yeah, I did go along with that. But the question is, for the future, what position do you take? And I’m not in favour of ID cards.”

“No, appreciated. But some people would say that for people who believe in civil liberties, 90-day detention – which just seems symbolic of everything, Habeas Corpus and so on – on principle you couldn’t possibly have voted for it. But you did vote for it.”

“Yeah but, I think that’s right, that’s true, but you face an obligation of loyalty as a member of a party and of a government. I’ve set out the direction I want to take our party in and people have to make a judgement about whether that direction is right or wrong.”

“I have one more question on the record then, which is not about Cabinet responsibility but about the manifesto. You were responsible for it, but there was no promise to the voter that you would do something about civil liberties.”

“No. I accept that as a criticism. And I take my responsibility for that. I don’t think that’s a strain that’s been a particularly strong… it’s sort of ironic because we did the Human Rights Act and we did gay and lesbian rights. But it hasn’t been a particularly strong strain in Labour and I accept my share of criticism for that. But I want to make it a much stronger strain going forward.”

“Do you regret anything about that manifesto?”

“Oh yeah, I mean, of course there are things you regret. I think it was a good manifesto. I actually think what we said about the minimum wage and public services and the future of our industrial economy was good. I don’t think we lost the election because of our manifesto, to be honest. I actually think the day of the manifesto launch was one of our good days in the election. I think we lost it for much deeper reasons, that people lost a sense of who we were and what we were for. But I take the issue that we didn’t renew enough in government. It’s much harder to renew in government. Some of that is because people didn’t want us to be radical and there were voices who didn’t want us to radical. But I take my share of responsibility for everything that happened in the last government, including the manifesto, but again it’s a question about the future really. Where does this party go in the future and what scale of change do we need?”

“Did you argue for more civil liberties in the manifesto at the time?”

“I mean, I’m not going to go into – because I’ve made a rule of this – into political kiss and tell, l if you like, of who said what to who. I take my responsibility. I was proud of our manifesto. I take responsibility for things people did and didn’t like about it.”

The demand for a more left-wing response to the political situation in the wake of the election has been interpreted in two different ways. Opponents, mostly New Labour royalty, brand it a typical retreat into the comfort zone in the wake of a depressing result. But others say it’s the wisest reaction to coalition government. There’s no room to the right of the coalition – the economic agenda is far too extreme for that. But the Lib Dems’ commitment to democratic reform and civil liberties seems to block off the left as well. The best tactic, therefore, would be to give leftie voters what the Lib Dems offer them – civil liberties and an ethical foreign policy – but without the nasty Thatcherite economic baggage the Tories are selling. There’s a conspiracy theory version of that assessment too. Some people say Labour knew what it was doing when it reacted so badly to the prospect of a coalition with the Lib Dems. It wanted to monopolise the left, and a Lib-Con alliance would allow it to do that.

Ed Miliband’s tactic, and the tactic of many of his colleagues, has been to attack the Lib Dems as the weak link – to prompt a falling-out between the party and its coalition partners. This has usually involved some harsh rhetoric. When he explained to Labour members why he was backing David Miliband for the leadership, left-wing figurehead Jon Cruddas specifically mentioned this as a major factor in his decision. He didn’t like such violent attacks on MPs that he considered fellow travellers of the left.

I ask Miliband exactly what he would have done if he’d been in Nick Clegg’s position after the election. He answers so quickly it eats up the end of my sentence.

“I would never have gone in with a Conservative government,” he rushes. “I’m not Conservative and what they’re doing on economics, on public services, is an ideological attempt to reshape Britain and I would never have been part of it. I could never, ever have imagined being part of it.”

It’s extremely genuine. “Wouldn’t the alternative have been another general election?” I ask. “Even a minority government would have needed Lib Dem support for the Budget, but you wouldn’t have done that.”

“In the end you’ve got to have some principles,” he says. “You’ve got to be willing to say: ‘OK there are certain things we’re willing to do to be part of coalition, but there are certain things we’re not willing to do’. Unfortunately in the talks I had with the Lib Dems they were actually hawks on the deficit. They were the ones saying – quite contrary to their position at the election – ‘we’ve got to cut now, we’ve got to cut deeply’. There is a very different strain of liberalism in this party. Clegg, David Laws – I have respect for them, but I respectfully disagree with them. I think they are basically small state liberals.”

“That comes down to something you’ve been talking about a lot recently, which is the distinction between the small state in civil liberty terms and in economics.”

“Exactly, exactly. We need to recognise we have a different electorate and to recognise we became too authoritarian in the way we thought about the state, too casual in the way we thought about the state. That’s why I’ve emphasised this tradition of liberty. There are a lot of people who wanted to vote for Nick Clegg who basically thought: ‘well Nick Clegg is offering us equality and liberty. Labour feels like its offering us equality but they’re too authoritarian for me’. What I’m saying is: Nick Clegg has offered inequality and liberty as part of this government. With me you don’t have to say ‘thank you for the end of ID cards but we’re going to have to have a reactionary assault on the welfare state’. With me, I’m saying, actually – we’ve got to be the people who are for liberty, but we’ve also got to be the people who are genuinely concerned with tackling inequality in our society.”

I’m interested in how far this leftward tack goes. His promise to get tough with the United States is basically in line with what every opposition leader promises before they take their first trip to Washington. Tony Blair, believe it or not, used to make critical comments too. What does it mean on a day-to-day basis?

“We saw in [the] Copenhagen [United Nations Convention on Climate Change summit] and the run-up to it that us being tough with the US on the issue of development aid for the poorest countries got results and I think it’s important to do that,” he answers. “For example on the Middle East and Israel-Palestine, they’re always going to have their particular view. We’ve got to have our particular view. So I was certainly outspoken at the time about the attack on the Gaza flotilla. We need to do that. The Gaza blockade needs to be lifted. You’ve got to be willing.”

He trails off for a moment, then adds: “This goes to the heart of my campaign. Some people say I want to go back to the 80s. I don’t want to return to the 80s. I want to move on from the assumptions of the 80s. It’s precisely the opposite to the charge that’s made. One of the assumptions about the Cold War was that if you departed from the American script you were anti-American and therefore part of the Soviet Union. I think there is a Foreign Office establishment view, which is that we are part of what they call the interagency process. You’ve got the National Security Agency, the State Department, and the British government. You’ve got to change that view. Yes, the relationship with the US is important but you’ve got to be stronger about saying we’ve got an independent foreign policy.”

This markedly more left-wing rhetoric is like the mirror image of Tony Blair’s rightward drift. I mention the former PM’s memoirs. “Essentially, it’s good timing for you for it to come out when it did, because it reminds Labour members that this is how far to the right the party went,” I suggest, to silence. I point out that Blair has disowned almost every liberal decision taken when he was in power, such as the Freedom of Information Act. “Is he even Labour anymore?”

Miliband laughs slightly. “Yes, of course he is. He’s deeply committed to the Labour party. He’s just got different views about its future. I just disagree with him that the reason we lost the last election was because of a higher top rate of tax on those earning over £150,000. Remember Tony Blair was a politician who came of age in the 1980s. It’s very, very hard to move on from those ghosts of the 1980s. A key question for the party at the next election is – can we move on from those ghosts?

“I don’t believe the public want us to say, ‘we’re not going to depart a millimetre from New Labour’. I don’t think that’s an election winning formula. We need to learn the lessons of New Labour, of appealing to all sections of society. But we’ve got to be willing to question some assumptions about flexible labour markets, for example, because too many were left in low paid work and thought we weren’t for them. I think it’s about having the courage to change and to move on and fundamentally that’s what my campaign is about.”

And with that, I’m told, my time is up. He’s awfully nice about it of course. On the walk back up Victoria Street to parliament, I wonder about his commitment to these causes he identifies his campaign with so closely. His comments about collective Cabinet responsibility are the standard response to issues of record, but they’re no weaker for it. He was well known to be profoundly loyal to the government, urging fellow Cabinet secretaries not to rebel against Gordon Brown in public. But the responses to questions about the manifesto were more evasive. I try to imagine him around the Cabinet table urging Brown to recognise civil liberties as an issue, but I can’t. That being said, I don’t doubt for a moment that these are his genuine views.

One thing is certain. If he does win, David Cameron will use the same attack against him that Campbell used. Nice, but too innocent. Too nice for politics. As Tony Blair explained in his memoirs – the effective attack against a political opponent doesn’t need to be exotic, it just needs to be believable. It is believable, as it happens, but probably false. There’s steel there too. We might be about to find out how much.