Prevent anti-extremism strategy creating ‘suspicion in the classroom’

The new obligation on teachers to refer pupils to police if they suspect them of extremism is creating a culture of “suspicion in the classroom”, teachers have warned.

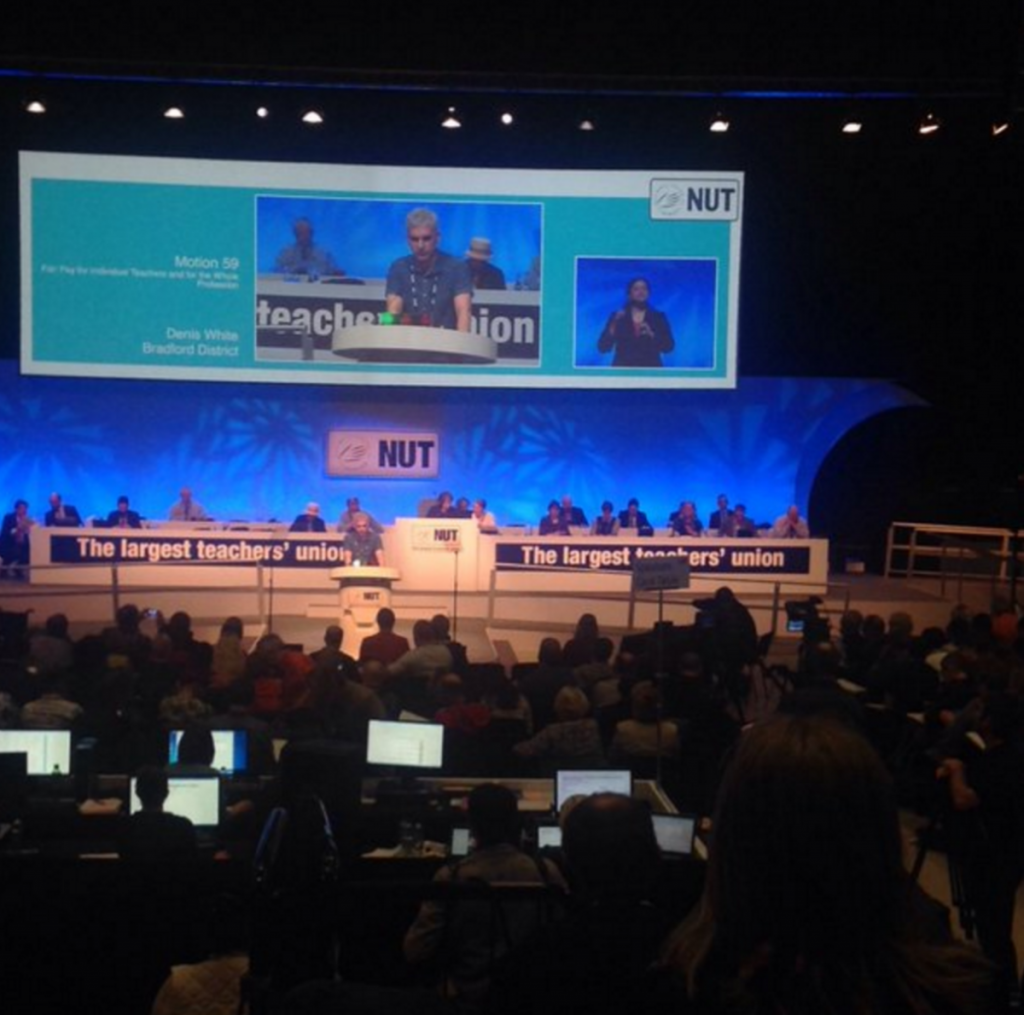

The National Union of Teachers (NUT) voted to scrap Prevent after a series of speakers complained that they were under-trained for its requirements and that schools were starting to stay away from controversial subjects for fear of having to act on comments made by pupils.

The vote comes after a report in the Times Educational Supplement that Prevent referrals from education are exceeding those from the police since the anti-extremism requirement was placed on schools last July.

“Some teachers are scared,” Nansi Ellis, assistant general secretary of the ATL teaching union, told the magazine.

“People are worried about what Ofsted is looking for. Are they looking for more referrals because of the duty, or fewer referrals because you are actually addressing these things?”

Speaking at the NUT conference yesterday, North Yorkshire delegate Gary Kaye complained of a simplistic approach from the government.

“I’m sure I’m not the only person in this conference hall today who has been given a sheet of A3 paper with a line that shows Isis on one side and the EDL on the other, as if the modern world of extremist political belief could be explained in such exact terms,” he said.

Kaye warned that the government was turning teachers into the “secret service of the public sector”.

The NUT supports the call by Indpt Reviewer of Terrorism Leg + many others for a review of Prevent https://t.co/6S41G7aaZL #NUT16

— NUT (@NUTonline) March 28, 2016

There are widespread fears among educational experts that Muslim children are being disproportionately targeted by the programme.

Last month a written submission to the home affairs committee from David Anderson, the independent reviewer of terrorism laws, stated that Prevent was a “significant source of grievance” among British Muslims.

“It is perverse that Prevent has become a more significant source of grievance in affected communities than the police and ministerial powers that are exercised,” he said.

“The lack of transparency in the operation of Prevent encourages rumour and mistrust to spread and to fester.”

Educational experts are looking warily at the experience in France, where last year’s Charlie Hebdo attacks were followed by a warning from education minister Najat Vallaud-Belkacem that “schools are in the front line” and government would “punish firmly”.

Teachers were obliged by the emergency Plan Vigipirate to report any pupil whose remarks could be interpreted as an “apologie du terrorisme”, leading to regular interventions by police following run-of-the-mill rebellious behaviour from teenagers.

Alex Kenny, the NUT executive member who moved the motion, told conference: “It’s leading to a situation where teachers are finding it more difficult to seize opportunities to discuss important issues.

“When that happens, we are in danger of abandoning young people to the dark places they can find elsewhere, on the internet and elsewhere, without any hope of any mediation by us.”

Delegates heard of a case in which a child writing about a ‘cucumber’ was misinterpreted as discussing a ‘cooker bomb’, while another describing a ‘terraced’ house was misinterpreted as discussing a ‘terrorist’ house.

A Department for Education spokeswoman said: “We make no apology for protecting children and young people from the risks of extremism and radicalisation.

“Prevent is playing a key role in identifying children at risk of radicalisation and supporting schools to intervene.

“Good schools will already have been safeguarding children from extremism and promoting fundamental British values long before this duty came into force.”