Ireland rejects EU treaty

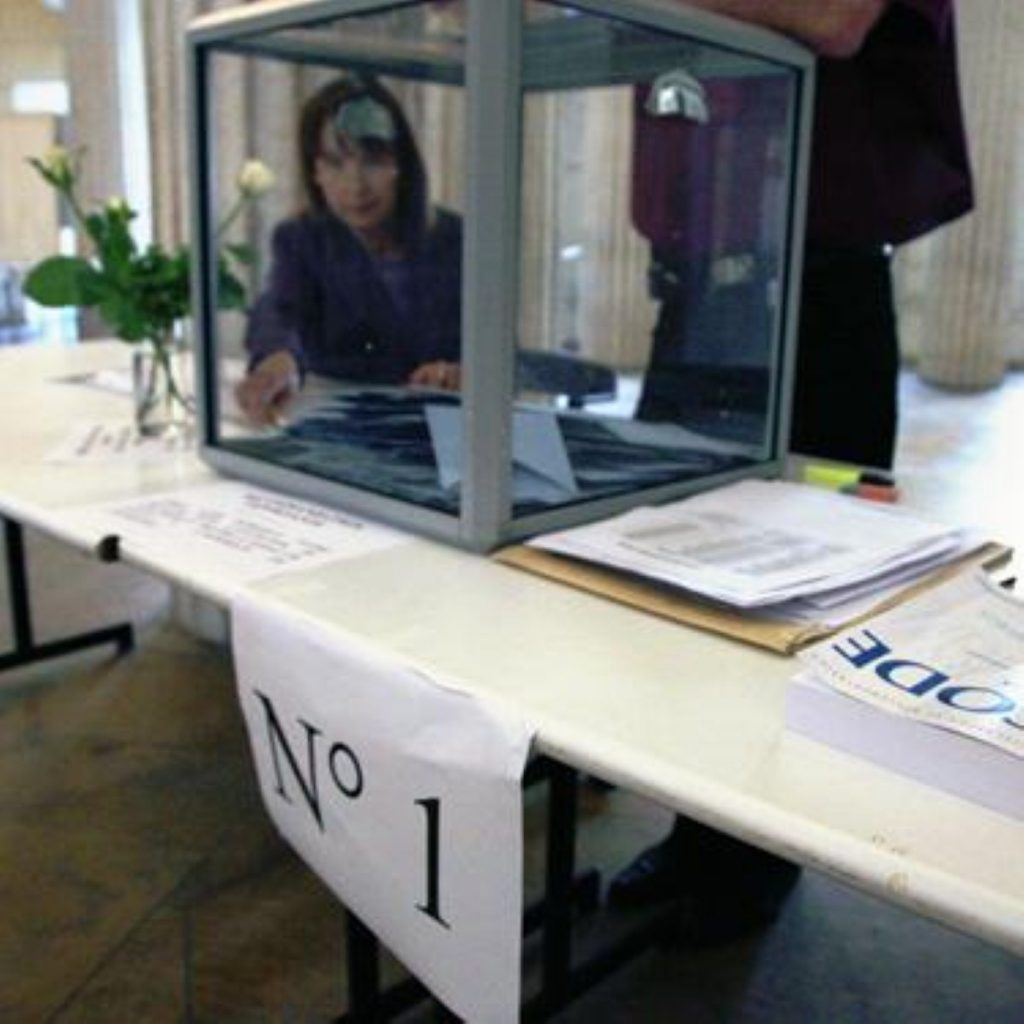

Ireland has officially rejected the EU Lisbon treaty, throwing the entire European project into continent-wide disarray.

The final tally was 752,451 votes for and 862,415 against with 53.4 per cent voting no.

Manuel Barroso, president of the European Commission said the Lisbon treaty is not dead following the Irish no vote.

“Twenty-seven member states signed the treaty,” he said. “We should not rush to conclusions.

Stressing the remaining countries would now meet to discuss the Ireland vote, he said: “The treaty is not dead. We should now try to find a solution. This wasn’t a vote against the EU.”

Irish prime minister Brian Cowen said the government accepted the verdict of his people but admitted the rejection was a “source of disappointment” and a “potential setback”.

“Once again in Europe, a treaty supported by the leaders of all member states has unable to secure popular support in a ballot. We must not rush to conclusions.”

He said the Irish government would be seeking to explain to EU officials the verdict does not mean it is now anti-EU.

Foreign secretary David Miliband said the result had to be “digested” and that Britain would not be pressuring Ireland on what to do next. He rejected calls that Britain suspend its own ratification of the treaty, which is expected to receive royal assent next week through the EU (amendments) bill.

“It’s right that we follow the view that each country must see the ratification process to a conclusion,” he said.

The vote is a momentous event in Irish and European politics, with the entire continental project being brought to a halt by a country with a population of only four million people.

A low turnout of 40 per cent – the minimum necessary to make the referendum valid – indicated a good result for the no camp.

The treaty needed to be ratified in all states for it to stand.

Despite a high-profile campaign by all main political parties, the ‘no’ camp found strength in the disparate objections and motivations of its members.

Anti-globalisation radicals, for instance, joined forces with anti-abortion Catholics to block the treaty and seem to have tapped into a relatively deep well of support.

Irish residents have a history of scuppering European projects. In 2001, voters rejected the Nice treaty, putting a temporary halt to the EU’s eastward expansion. A second vote meant the treaty passed, although with some considerable objection.

Ireland is the only country holding a referendum on the treaty; should the no camp win it will be the third time countries given an option over Europe roundly reject it.

The French and Dutch electorates voted against a European constitution in 2005.